I first arrived in China in March 2001, round-eyed, full of trepidation and ready for a range of exciting adventures. Less than one week later I was sat in a hospital in Xi’an with a drip in my arm. ‘So much for Chinese traditional medicine!’ I thought. As it turned out, this was to be the first step in an endless process of realigning my expectations.

What Happen

The rather unexpected medical turn of events was, actually, quite unrelated to China itself. Apparently, a few weeks earlier, whilst on holiday in Portugal, I’d been bitten on the shoulder by an Unidentified Flying Organism. The bite later became infected and poisoned my system. On an otherwise sunny Sunday morning in Portugal, I’d started to feel decidedly under-the-weather. I headed for the nearest pharmacy in an attempt to get some antiseptic cream for the, now festering, wound.

I initially thought that this would be a reasonably simple process. Boy was I ever wrong…

After 15 minutes of pointing at tubes of cream, frantically rubbing myself and shouting ‘Antiseptic’ in a gradually increasing pitch and volume, I was still getting nowhere. I tried racing around the room, flapping my arms, whilst buzzing and doing my best impression of a giant manic insect. When my final strategy of pointing at the wound, biting myself and screaming ‘ANTISEPTIC!’ at the top of my voice, failed to work, I left exhausted and empty handed.

I spent a restless, feverish evening, becoming increasingly worried about the infection and berating myself for my complete ineptitude at Portuguese charades. In the morning, as soon as I could stagger to the Tourist Information Office, I asked the assistant to tell me the correct Portuguese word for ‘antiseptic’. My rather sweaty and feverish little body was all a-quiver in anticipation of learning the magic word.

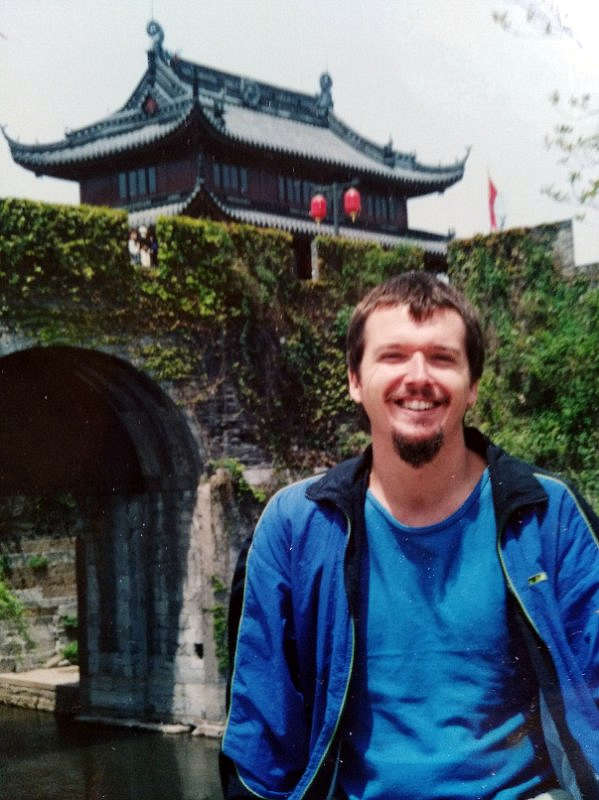

(One of my fiirst photos in China - almost 20 years ago!!!)

‘Antiseptiko’ was the much-awaited reply.

‘What? This must be a joke’, I thought. It sounded uncannily like the English word with the letter ‘o’ shoved on the end. After having the magical word repeated to me a few times, I headed back to the pharmacy, ready for failure. Once there I pointed wearily at my arm and said ‘antiseptic-oh?’ The pharmacist smiled knowingly, said something that I guess was the Portuguese equivalent of ‘no worries’ and 10 seconds later I had a tube of cream in my hand. I sat down and applied the cream to the bite, over a cup of ‘coffee-oh’.

By this stage the damage was already done and I was quite sick. I chose to ignore this fact, and headed for China. From this experience I learned just how difficult something simple can be when unable to speak the language. I, therefore, spent most of my lengthy flight to China scrutinizing my phrase book and trying (unsuccessfully) to say the word ‘ma’ in four different tones. No amount of foot stomping or eyebrow raising, which the book recommended, could help me get it right. But my constant ‘maa-ma-maaing’, reminiscent of a flock of sheep, successfully put my fellow passengers to sleep.

In some ways this ‘trying to understand’ and ‘be understood’, was to become the theme for my early travels around China.

So, in Xi’an, still in my first week in China the wound on my shoulder had yet to heal, when I got two tiny cuts on my wrist. An hour later I had two purple lines progressing ominously from my wrist towards my heart. ‘Once bitten, twice shy’, I figured and decided to hot foot it to the hospital. It was all a lot easier than in Portugal: I showed my passport; paid a small deposit; and was sat in a doctor’s surgery within half an hour. Five minutes later, after much concern and a flurry of lab coats, a team of four medical personnel wheeled in, what has to be, the world’s largest bilingual medical encyclopaedia.

I was sent with a slip of paper down to the dispensary whilst the doctors pored over the gargantuan book. I returned with an armload of medical supplies, much of which (alarmingly) seemed to involve needles, to find the doctors exhausted. The livelier of the bunch lead me over to the book-of-all-knowledge and referred me to three separate entries. These were: Septicaemia; Blood Poisoning; and Lymphocymia (I don’t even think the last one is a real word). I was then informed that I was at Death’s door and fast action was required.

I spent the two hours I was sat with a drip in my arm resolving to become fluent in Chinese to prevent any future misunderstandings. But this turned out to be more difficult than anticipated. A language with four tones is difficult enough to master. But throw into the mix a vast country with distinctive regional variations of dialect and it becomes almost impossible to master. I felt determined to learn the language and not just resort to pointing at sentences in my phrasebook. Therefore, when I knew I was going to need a certain phrase, I would sit and scrutinise the relevant page in my phrasebook, practising the tones by reading out loud. I would then chant it like a mantra as I approached the person with whom I was to speak.

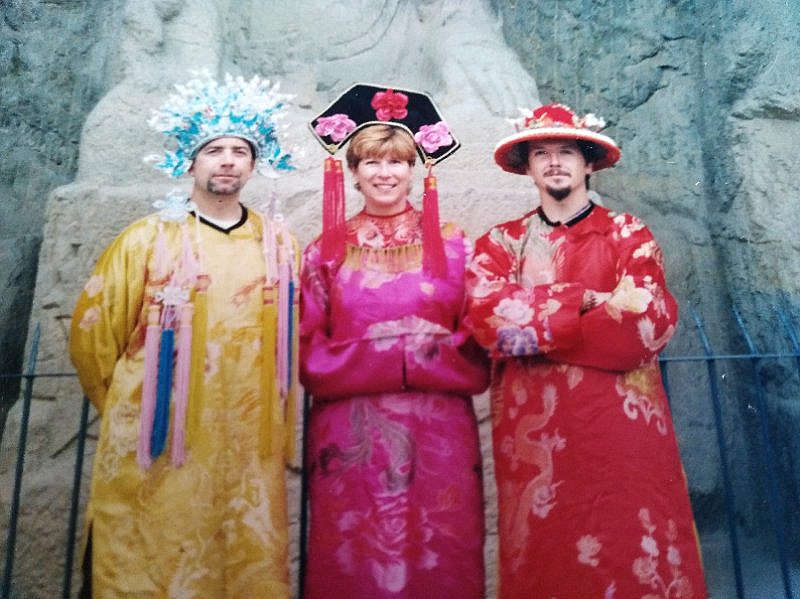

(We are "kings" and "Queen")

Begin Learning Chinese

‘Ni you meiyou Yingwende shu?’ (Do you have English books?) I proudly asked a sales assistant in a bookshop, pointing at a book. I didn’t receive the flicker of recognition I was hoping for.

‘Ni you meiyou Yingwende shu?’ I enquired, picking up a book. I repeated the sentence once more pointing at the book more vigorously, but was still receiving a pretty blank stare. I decided to try jumbling the words up a bit.

‘Shu?’ ‘Yingwen?’ Still nothing! ‘You meiyou?’ I asked, slapping the book a bit manically at that stage and probably shouting the words a little loudly.

I then launched into a small performance, involving me relaxing, happily in an armchair reading a book. I was drawing a total blank. Not even the vaguest hint of emotion.

I decided to give up and leave.

Outside in the street I sat down and tried to build up enough enthusiasm to have another go. I hadn’t been sat for long, when a Chinese student appeared. She said ‘Hello!’ and asked if she could practise her English with me. A little over-enthusiastically I leapt up, shouted ‘Yes, of course!’ and dragged her into the bookshop. Once inside, I explained that I wanted to buy a book in English and repeated the phrase I had learned in Chinese. The student nodded and turned towards the sales assistant.

‘Ni you meiyou Yingwende shu?’ she asked.

‘Meiyou’ (Don’t have), was the reply.

I was flummoxed. I was sure I had said exactly what she’d said. I’d even raised my eyebrows, stomped my feet and waved my finger around to indicate the different tones. I asked the Chinese student why the assistant hadn’t understood me. She asked me to repeat the sentence in Chinese.

‘When foreigners ask questions they always raise the tone at the end of the sentence to denote enquiry’ she informed me, in what seemed embarrassingly like an English lesson. ‘This changes the meaning of the last word. The way you pronounce ‘shu’ it sounds like mouse!’

Ok, but why would I be in a bookstore, pointing at a book, asking if they had any English mice…?

Despite endless setbacks I did persevere. Whilst it was usually alright on the night, there were occasions when I would get a bowl of soup instead of sugar for my coffee, cigarettes instead of salt, and a fish head instead of taro for dinner. Fortunately most of the people I encountered in China demonstrated vastly more patience than I did and I’m proud to say I can now confidently walk into a bookshop without the fear of buying a mouse.